(Winner of the Mental Health for Romania Art Contest, prose category)

If her aunt was in a good mood, Aura would sometimes let her sit with her in her parents’ bedroom and watch a movie or TV show together. Her small child’s body was lying on the bed, supported by a heap made of big, firm pillows stuffed with goose feathers, watching TV and holding the remote control, while her aunt, Aunt Mari – as all the nephews called her – was sitting on the edge of the bed, with the child’s legs stretched out in her lap. Her hair was somewhere between a shade of gray and grayish-white, cut short, kind of boyish. She wasn’t wearing earrings, but Aura remembered seeing her wearing large amber beads and oversized sunglasses with yellow frames and tinted lenses under a large white cloth hat to shield her head from the sun.

In her youth, Aura’s aunt had been a beautiful woman with a slender waist and long, silky hair, always wearing elegant clothes in the fashion of the time, as Aura had seen her in a photo from the civil wedding party, where the younger version of Aura was dancing relaxed. Now, depending on her mood, she often wore either a long skirt drawn almost to her breasts and a milky blouse, or – when in a belligerent mood – a washed green army shirt that she couldn’t seem to part with. She smelled of cigarette smoke all the time, because she smoked a lot, including at night, and the fingers and fingernails on her right hand were yellowed from all the tar. Aura had noticed on several occasions that they were yellowed when the woman asked her to cut her nails outside in the courtyard. She did that too, even if it wasn’t a particularly enjoyable activity, but she quickly got over it. While cutting her nails, she noticed that on one of her fingers her aunt was wearing a white plastic ring, which was detached from a small tube containing the drops she took daily. Sometimes, Aura’s aunt also carried a black lacquer purse on her arm, in which the child suspected she kept her lipstick – it had always been a mystery to her childish mind how lipstick that is green when taken out of the tube turns red on her aunt’s lips. Also in this purse, Aunt Mari kept a toy pistol and many other things.

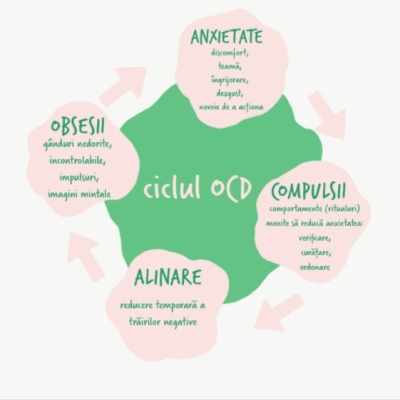

The only reason Aura let her sit and watch TV was because she had her massage her legs – oh, and what a massage she gave her feet and calves! Vigorous, powerful, comforting movements. It was a real godsend for the child, who enjoyed this pampering that she didn’t get from other family members. But soon after they started to watch TV together, Aunt Mari slipped into a hazy slope of the mind and poured out some nonsense that had become part of the home landscape and to which Aura had become immune. In other words, she didn’t pay much attention to them after a while: “This is me when I was younger”, “This is Ionel when he was younger”, she used to say, referring to her brother, that is, to Aura’s father. Any movie actor or actress, any TV star or presenter, any politician who appeared on the small screen was automatically accompanied by a remark from her aunt, spoken in a hoarse voice – the result of decades of smoking unfiltered cigarettes from the packets that Aura’s grandmother kept hidden in a huge pocket of her kitchen apron. She was the one who offered cigarettes to her aunt and never handed her a whole pack. It was also her grandmother who, as Aura had seen so many times, gave her aunt her medicine regularly: in the morning, at noon and in the evening. Words such as “treatment”, “drops”, “prescription”, “Haloperidol” were uttered by the old lady and caught on the fly by the child, so that one day, when she was younger and playing doctor at kindergarten, the teacher overheard her prescribing the puppet-patient a little “Haloperidol”.

Now it was summer, and the heat had made everyone in the house retreat to the cool of their rooms behind the drawn blinds. The flies were buzzing in the kitchen, despite Aura’s mother’s best efforts, using expensive sprays and yellowish strips of sticky glue to stick the poor flies’ legs and wings. The hall that connected the kitchen and the front door of the house led to a parlor, and here, on two large cement steps covered with a crossbeam, Aunt Mari spent most of her time smoking, eating watermelon and talking nonsense. Most of the time, the woman didn’t sleep at night and stayed on those two steps until dawn, and in all those hours of the night her mouth didn’t stop at all, babbling some words jumbled in the whirl of neurons, under the influence of the treatment and sleepless nights.

Of course, during the day, she didn’t just stay in the house, as the child had noticed so many times when she played in the yard or in the garden. She had seen her aunt in many situations over the years and they all seemed normal to her. She thought that everyone had an Auntie Mari at home. On clear summer days, the woman pointed a toy pistol, either wooden or plastic, stolen from Aura’s older brother, at the sky, firing full force at enemy rockets that any sane person would see as the white trails created by the engines of airplanes in flight. And she kept firing and firing in these trails made by airplanes, reproducing the specific sounds, until they disappeared from the sky and only then could Aunt Aura breathe a sigh of relief, because she had saved them all from death.

In other situations, she would catch the woman picking up the receiver of the landline phone in the kitchen and, without dialing a number on the telephone’s wheel, she would shout in a loud, hoarse voice: “Hello! The public prosecutor’s office! The public prosecutor’s office! Pascu Paraschiva will kill me!”. Then she would hang up the phone, slamming the receiver on the hook, and she would go out, where she would continue her string of words, asking for help from the prosecutors and passers-by, saying that “Pascu Paraschiva” was trying to kill her, until she was hoarse from all the screaming. When she grew up, Aura realized that Pascu Paraschiva was actually her grandmother’s maiden name, but no one called her “Paraschiva”. All her grandchildren called her “mamaia Georgeta”, after a nickname their grandfather had given her when they were young. Only Aura’s aunt, during her seizures and hallucinations, which became even more frequent in the summer months, called her by the name that had become synonymous with that of a dangerous criminal.

Aura grew up with bits and pieces of information about her aunt, like pieces of an extremely complicated puzzle, which never stay the same, which seem to change from one day to the next, just as their aunt’s mood seemed to change, who today seemed to love them, tomorrow was cursing them at the top of her lungs, scolding them and shouting at them that they were “Bulgarian brats”. The child had never wondered about the woman’s condition, and no one had ever explained to her what the illness was that Aunt Mari had suffered from since her youth, after a disappointment in love. She knew that the summer was an unpleasant time for her aunt, because “crises” appeared, that she became a danger for herself and for their grandmother and that Aunt Mari had to be hospitalized in a hospital in Bucharest, from where she returned home, after a few weeks, a little calmer.

There were also days when the aunt slept a lot, and hardly saw her in the yard or around the house. There were times when the woman confessed that her natural parents were Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu, but to the child it seemed hard to understand how two figures she had heard about on TV could actually be her aunt’s parents. On top of all this, she also remembered some funny moments she had witnessed as a child. For example, when a close cousin of Aura’s father’s came to visit them one summer – an elegant, well-groomed woman in her late 50s – her aunt approached her, put her hand on her protruding belly and said in a serious, matter-of-fact tone: “You’re pregnant, ma’am, you’re pregnant!”. Often, however, the spiteful or angry remarks were directed at the one who had over the years become the main target of her aunt’s verbal attacks, namely Pascu Paraschiva. The old woman – God bless her! – had not had many days of peace in the company of her daughter since she had fallen ill with her mind, and the phrase that stuck in Aura’s mind and was uttered most often in their home – second only to “Pascu Paraschiva is killing me!” – was the eternal “You’re crazy, lady! Can’t you see you’re crazy?”

*A portrait of my aunt, with whom I lived in the same house. My aunt was suffering from schizophrenia, as can be seen in the portrait/short prose, and when I was a child, all those things she did seemed normal to me.*